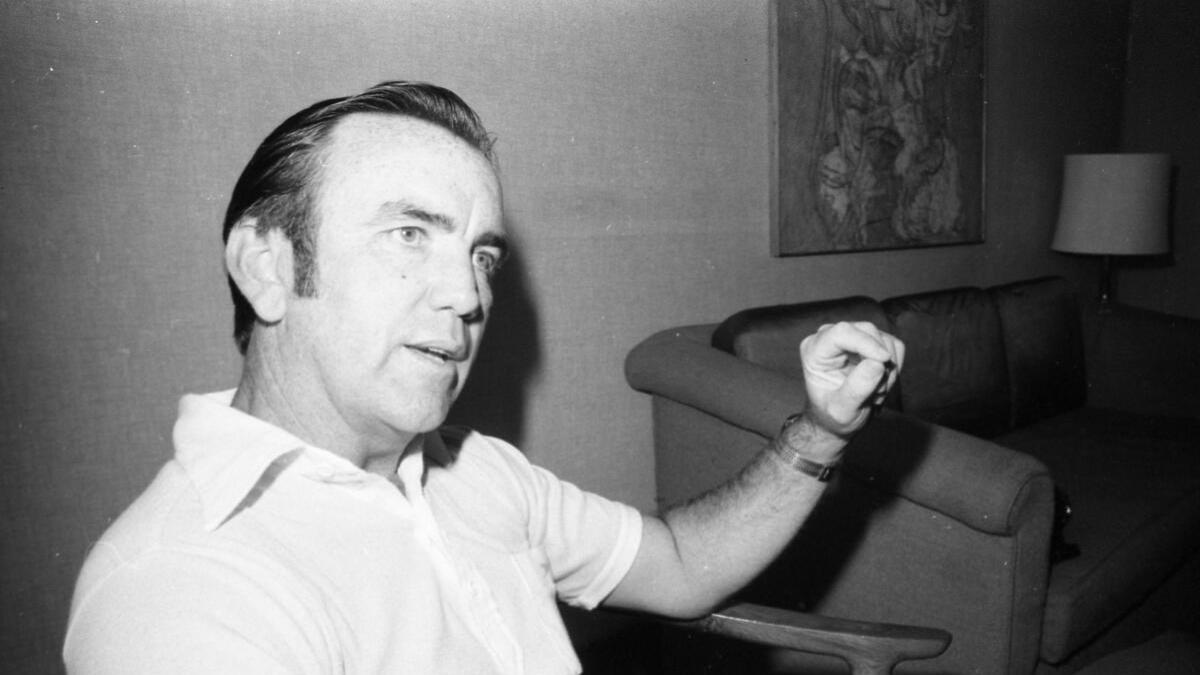

Former Australian cricket team captain and coach Bob Simpson passed away on Saturday, aged 89.

Simpson made an indelible mark on the game as an opening batter, brilliant slips fielder and handy leg spinner; and as a respected and long-serving coach, including of the Australian men’s team.

The legendary Aussie also penned a widely loved column for Sportstar in the 2000s called Cricket Corner, which involved his take on erstwhile issues facing the game globally. Here are some from the vault:

No point in comparing different eras [March 11,2000]

There has been much conjecture in recent months about just how good the current Australian team is and where they rank in the best ever Aussie squad. Steve Waugh is on record as saying he believes they are up with the best, including the 1948 Bradman Invincibles. He also claims that the present group are the best one-day team that he has played with. This is a natural thing for a captain to suggest, but I believe that he may be just carried away a bit.

Certainly, this is a fine era in Australian cricket and they have performed creditably since winning the World Cup. But the best he has played in! That is another matter, particularly when the three most senior players, Shane Warne, Steve and Mark Waugh, are not playing as well as they used to. In Steve’s case he was, in my view, one of the finest one-day bowlers I have ever seen and undoubtedly the best in the death overs. These days he hardly bowls at all and he has only scored one 50 since the World Cup in one-day internationals. Mark Waugh has also struggled for most of the season with the bat, while Shane Warne is a good rather than a great bowler he was only a couple of years ago.

With the present programming I have grave doubts whether present teams will ever reach the allround performance of the past. These days teams are not allowed the luxury of acclimatising to the conditions in overseas countries. At one time when tours were longer, teams arrived early and played five or six first class matches in the new country before the first Test and had a chance to get used to local conditions.

The excellent West Indies of 1960-61 were a classic example of how extra time enabled a team to come to terms with foreign conditions. They arrived in Australia with a big reputation, but didn’t win a match when they visited the five mainland States before the first Test. Their form and attitude were terrible and so worried were the Australian cricket Board that Sir Donald Bradman, the then Chairman of the Australian selectors, sought Richie Benaud’s permission to speak to the Test team at our dinner the night before the first Test.

His message to us was very clear: Australian cricket is in the doldrums, the West Indies are in terrible trouble, we need a good series and I want this team to play the most entertaining cricket possible. He wasn’t suggesting that we take it easy, just play attractive cricket. He needn’t have worried. The West Indies adapted to the local conditions, played brilliantly in the first Test of the series and the 1960-61 tour was perhaps the best ever.

These days it is a different situation with the programming allowing the teams only a minimum number of games before the first Test, generally one or two, particularly in the sub-continent. As a result they find it very difficult to play well early. This has been already demonstrated on Australia’s last tour to India and Sri Lanka. India easily accounted for them in the first two Tests and it was only in the third when it was far too late that Australia played well and won a belated victory. It was much the same in Sri Lanka. The home team easily won the first Test in Kandy, were on top in the second when rain washed out play and it was only in the third and last Test that Australia got on top before rain again washed out play.

Australia dominated both India and Pakistan in Australia, but battled to a 3-2 win against the weak West Indies in the Windies in early 1999. A realistic look at these performances shows it hasn’t always been one way for the Australians. They have dominated with a wonderful new ball attack on the faster Australian pitches, but our batsmen have struggled on the slower and often turning wickets overseas.

In many ways present day Test players get it tougher than the teams of the past. They are certainly better paid and often get a chance to build up personal performances against the new and weaker Test nations, but frequent tours to almost every part of the cricketing world with inadequate preparation can make it very difficult. It is brilliant when a player is in form and prospering, but very tough when you are out of sorts and on foreign often difficult local pitches.

That, however, is also why it is impossible to compare one era with another. I have always thought it was a useless exercise and never have done it. There are too many different factors involved, such as playing conditions, strength of the opposition, weather and changes in the laws. My attitude always has been, ‘let’s enjoy the spectacle and skill of the modern players, for that is what we have on display’ and no matter what some old-timers may say, they are generally pretty good.

1985 was the beginning of explosion [February 3, 2001]

It appears that every second day or so a record is broken in international cricket.

No, make that more definite, a record is broken every few days. Such is the volume of international cricket now being played.

This of course is immensely helped by the new countries that have been admitted to the International brotherhood. I, for instance, never even have played a Test match against New Zealand. Such was the arrogance and insular attitude of the Australian Cricket Board that they deemed New Zealand not good enough to play against Australia even though other nations had been playing against them for decades. In fact, it wasn’t until the 70s that international cricket was regularly played between New Zealand and Australia.

Zimbabwe, then Rhodesia, even though they were a separate country, played in the South African local first class competition and the likes of Colin Bland, perhaps the finest field- represented South Africa.

Bangladesh in my time was still part of Pakistan, while Sri Lanka or Ceylon as it was then known, was only a place to play cricket when the ship stopped for eight hours or so on the way to England.

Now, of course, all these countries are full fledged international competitors with varying standards. How then are records and statistics relevant both at Test and One-Dayers level? Vary according to the coverage it receives in the media.

As a comparison basis, however, probably not as useful as it was in the past. At one time, it was said, and probably quite accurately, that if a player averaged a certain figure in one era he would probably do it in another, I could accept this, for with the lengthy time I spent in cricket I felt I was reasonably equipped to judge whether a player who averaged say 45 per innings in the fifties was the equal of another player who averaged the same in the seventies. As a general rule I would say yes.

Now I am less sure, for it is much harder to judge with so many weaker countries around and the extraordinary number of not outs secured by the batsmen.

For instance, Don Bradman was not out every eight innings and Gary Sobers every 7.6, while Allan Border was not out every 6 innings and Stephen Waugh every 5 innings. Obviously the more not outs the better the average.

Personally I feel there should be a cut out system with two groups, those who finished their careers say before 1985 and those after. Nineteen eighty five was the beginning of the explosion and also about the start of the introduction of new teams. It would also. I believe, be a more accurate showcase of comparison of players’ talents, for batsmen as well as the bowlers.

It is generally agreed that it is almost impossible to compare eras and I have always refused to do this or even try to select the best team ever, for I always felt it was a pretty futile exercise. Conditions, rules, circumstances change so much. For instance, up to the middle 30s batsmen could only be out LBW if the ball pitched on the stumps. Now of course you can be out LBW if the ball pitches outside the off stump and the batsman is struck in front of the stumps. This was a big plus for the bowlers.

On the other hand wickets were uncovered so bowlers often had the advantage of sticky dogs to bowl on. New balls were not always taken after 80 overs or so and in the late 40s the new ball was taken every 40, eight-ball overs.

In the 30s, often referred to as the Golden Age of cricket, Sir Donald Bradman told me the pitches were as perfect for batting as he had ever seen. Now wickets generally have deteriorated and countries are more inclined to fiddle the surface for a home team advantage. Balls have changed or rather the seam has been altered and in England in particular, the seam has been lowered and raised, particularly in the last two decades or so. Now, of course, we have a third umpire in the international scene being called on to make judgment on certain types of dismissals, such as run outs and stumping. I personally find this a very equitable situation.

Undoubtedly, international umpires and referees have helped raise the standard of umpiring throughout the world and claims of bias in away series are much more muted than they once were. Comparisons of averages and aggregates are generally futile, for they are so affected by the above points but they can often be intriguing. For instance, if we took the average of a batsman as a starting point and used it in comparison with players from one period to another it is quite revealing.

For instance, if Bradman played as many innings as Allan Border using the above premise, he would have scored 26,484 runs. Sir Garfield Sobers would have scored 15,311 runs and Viv Richards 13,271. Now what about a comparison of the greatest all rounder ever – Sir Garfield Sobers. I will use, as a comparison once again, Allan Border’s long career.

Allan Border played in 156 Tests, the most ever so I will use this as the bench mark and average out Sobers _ wickets and catches as if he played as many Tests as 3 AB. m Sobers took 109 catches in 93 Tests, an average Z of 1.17’2 per Test. If he had played 150 Tests he would have taken 182 catches. Bowling in 93 Tests, Sobers took 235 wickets an average of 2.526 per Test. Once again if he had played the same number of Tests as Border he would have taken 394 wickets. Just think about it: Sobers, G. 15,311 runs. “ “ 394 wickets. “ “ 182 catches.

Can you imagine just how much hype those figures would create today? But you cannot compare or can you when you are talking about a genius like Sir Garfield Sobers?

BCCI’s decision needs to be complimented

The Board of Control for Cricket in India is to be congratulated on its decision to ban one-day cricket for players under 17 years of age. In doing so, the BCCI is leading the world in the restoration of not only spinning skills, but also in batting and swing bowling. I must admit that I am surprised that the administrators of Indian cricket have made this decision, for it has seemed to me that they were too anxious to milk the cash flow of the ODI’s to the detriment of the skills and future of the game.

While the BCCI has specifically targeted the woes of spinners in limited overs cricket, I feel it has also had a negative effect on swing bowling and batting and indeed the overall quality of cricket. As an Australian I am delighted that we are dominating world cricket, but I am less than happy with the standard of world cricket and the present era may well be the poorest I have seen in my 50 year involvement in first class cricket.

It is of course an easy call to heap all the woes of present day cricket on the limited overs game.

This is obviously not the case as the instant version has still an enormous role to play in our game. To my eyes the biggest worry about the introduction of limited over matches was not the separate competition aspect for which it was developed, but how it was promoted to replace traditional matches where one team had to bowl the opposition out and then score more runs to win the match. The most important aspect was to learn how to dismiss the opposition and not allow the match to be won by pure containment.

The one-day format was allowed to permeate all aspects below the first class fixtures. At one stage even our grade or district cricket, the level below first class was played to a limited over format. The time frame in district cricket was up to 100 overs per session.

Most of our cricket in those days was played over two Saturdays and 100 overs was what the administrators were looking for each Saturday. Within a very short time captains were concentrating on containment and while they might look for wickets with the new ball they settled quickly into negative style bowling.

Any style which needed to attack to get wickets was considered a liability and spinners, leg spinners in particular and swing bowlers paid the penalty. Our district cricket became an afternoon of attrition and skills quickly fell away.

Fortunately, after about 10 years, wiser counsel prevailed and the old system was restored. Unfortunately, by this time, the damage was done and leg spin and swing bowling were forgotten. When attempts to remedy this were introduced they were stalled badly by the current captains having no idea whatsoever how to handle leg spinners or swing bowlers and it if they were hit for a four or two they were quickly removed from the attack and bowling short of a length medium pacers with little ability to take wickets replaced them.

Unfortunately limited over cricket was also introduced into local park competitions (where allAustralian cricketers emerge from) and under age matches. As a result, this boring negative form of bowling, aided by some incredible new wave coaching (theories, fads and fashions) saw batsmen drift away from the basic fundamentals which had served the masters of the past like Bradman, Hobbs, Hutton, Gavaskar, Sobers and Greg Chappell, so well and were all but forgotten. Australia was badly affected by this and the early 80s saw a drop in the standard of the Australian team where too many players didn’t have the skills or perhaps coaching to bowl line and length or the concentration to play long innings. Not surprising we slipped to the bottom layer of world cricket.

In the middle 80s we undertook a plan to restore common sense, at least at the international level, in Australian cricket.

Interestingly, we targeted one-day cricket as our best chance of getting a result. I have always believed that there shouldn’t be a great difference between limited over matches and normal cricket and I set out to take the slather and whack out of one-day cricket and also restore greater emphasis on taking wickets.

Australians have always had a penchant for attacking cricket, but unfortunately had forgotten that you also had to be disciplined in following this direction.

We were relying too much on big shots and ignoring what was always the bread and butter of Australian batting, and that was taking quick annoying singles and running betwee wickets quicker and better than any nation in the world.

We went back to the basics concentrated on dotting the I’s and crossing the T’s. It took time, but the players accepted the old-new ideas and realised they were quickly learning. Our 1987 World Cup victory was the turning point and the confidence we gained from that win gave us the impetus to dominate one-day cricket for the next four years and time to continually improve our Test cricket.

Interestingly we almost became too good and received criticism in the media of being too clinical and boring even though we were scoring our runs at a very good rate and winning the majority of matches by bowling the opposition out and not relying on containment. My reply to this criticism was simple and I related it to my other great sporting love, golf. In golf if a player splits the fairway hits his second close to the pin and sinks the put with regularity he is described as brilliant, close to perfection and thrilling.

This is exactly what we were doing and while it may have been more predictable than other teams it was also very skilful and classy. Personally I am finding Test and one-day cricket too predictable as teams with the exception of Australia are all using the same tactics and most of them with little success and consistency.

I just hope India’s initiative has a follow and other nations adopt it to get the best out of the natural talents, individual styles and strengths of the various countries. If they don’t we may as well clone every cricketer and make them play on the same type of synthetic wicket.

That is the way coaching seems to be heading, as most countries seem to be looking for a master plan to clone their players without allowing natural talent and style to emerge. For after all aren’t these differences that set apart the great players from the ordinary?