Jack Russell is a busy man. In one of the posh lanes of central London, he pursues his passion — painting portraits — a profession he’s embraced for more than three decades. The former England wicketkeeper is now an acclaimed artist and runs a premier art gallery. When in London, he makes it a point to be at the Chris Beetles Gallery, where his cricket-themed artworks evoke nostalgia.

At 61, Russell travels around the country, capturing landscapes on canvas. He avoids mobile phones, preferring email for communication. Yet, even amid brushes and canvases, cricket remains close to his heart. Whenever the topic comes up, you can see the glint in his eyes.

“I still love cricket. But it’s just that painting is the only skill I can do now because I can’t play anymore. I’ve been a professional artist longer than I was a cricketer. So, that’s how I’ve ended up earning more money because I’ve done it for a longer period of time,” he tells Sportstar with a smile.

Russell is impressed with Rishabh Pant’s grit, batting through a broken foot in Manchester. Yet, such batting heroics cannot hide a wider concern — that the art of wicketkeeping is on the decline, with players focusing more on run-scoring than refining their glovework.

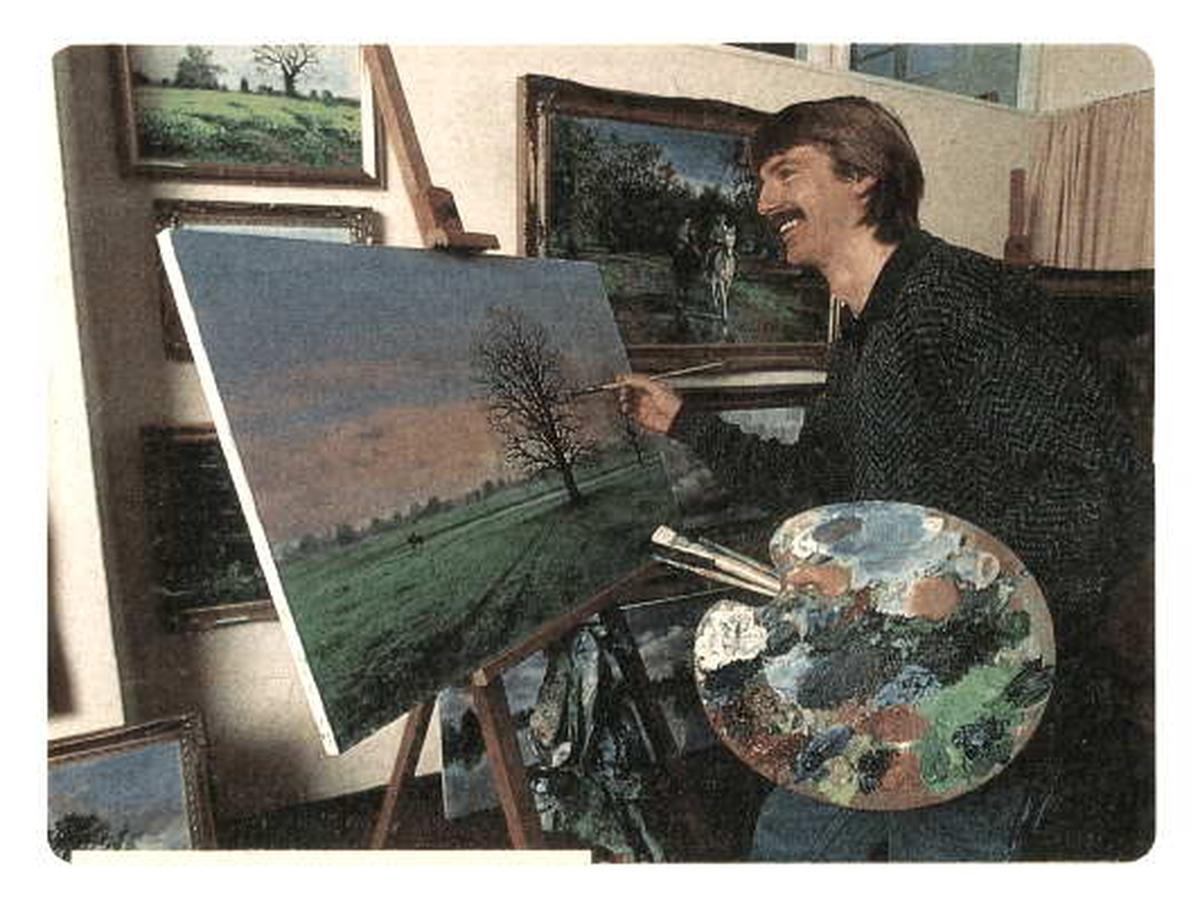

Jack Russell was as evocative with a paintbrush as he was deft behind the stumps, turning both canvas and cricket field into stages for his artistry.

| Photo Credit:

THE HINDU ARCHIVES

Jack Russell was as evocative with a paintbrush as he was deft behind the stumps, turning both canvas and cricket field into stages for his artistry.

| Photo Credit:

THE HINDU ARCHIVES

“It has been like this for a while. It’s just the norm now. They look at batters first, and wicketkeeping is secondary. So, that’s just what all the teams are doing now. That’s just the way it is,” he says.

During his playing days, Russell was replaced by Alec Stewart, as selectors preferred a stronger batter who could also keep wickets. Despite featuring in 54 Tests and 40 ODIs, Russell eventually faded from the international scene.

He believes this tradition continues. “But that’s fraught with danger because mistakes are often made. They think it’s a shortcut, but as a wicketkeeper, you have got to be so careful. If you miss skill, then you’re going to pay the price,” he says.

“The thing about the wicketkeeper now is that he doesn’t just have to score runs, but it’s the way he scores the runs. He has to be a bit like (Adam) Gilchrist, who would attack right from the start. So, you have to be powerful, and you really have to be like an aggressive top-order batter.”

He admits Pant is hard to look away from at the crease but says the Indian ‘keeper-batter has flaws that could cost him over time. “He is a great talent because it’s interesting to watch Pant. You have to watch him play. So, that’s good for the spectator. But then, if you look closely, he will make mistakes because of the way he keeps wickets. You have to accept that,” he says, adding, “But the fact that he can be so devastating with the bat makes him one of the most entertaining players in the world to watch…”

Russell recalls carrying a canvas and paint box on overseas tours, never imagining painting would become his profession. Cricket, however, remains his first love. When the conversation turns to wicketkeeping, the mood shifts.

He admits the craft has “been in danger for a long time,” and that pains him. “Probably, I wouldn’t have played now, as they would not have picked me because I don’t hit enough sixes. The art of wicketkeeping is lost because there’s actually a lack of understanding about the importance of wicketkeeping,” he says.

“It has been going on for a long time. It has been like 30 years or maybe longer. They (the selectors and the team management) think they’ve been clever in taking shortcuts. But it comes back to haunt you at some point. Pant missed a couple of chances, and in normal situations, those catches should have been taken.

“In our times, we were always taught that a wicketkeeper cannot afford to drop catches of Vivian Richards, Brian Lara, Sachin Tendulkar, Ricky Ponting, or even a Matthew Hayden. The list is endless. You must make sure that you don’t make mistakes, because if you do so, those batters will make you pay the price,” Russell says with a wry smile.

In the summer of 1992 at Old Trafford, Pakistan’s Wasim Akram ventured down the pitch once too often — and England’s Jack Russell was waiting. With a flash of the gloves, Russell whipped off the bails to complete a sharp stumping during the third Test. The match eventually ended in a draw.

| Photo Credit:

THE HINDU ARCHIVES

In the summer of 1992 at Old Trafford, Pakistan’s Wasim Akram ventured down the pitch once too often — and England’s Jack Russell was waiting. With a flash of the gloves, Russell whipped off the bails to complete a sharp stumping during the third Test. The match eventually ended in a draw.

| Photo Credit:

THE HINDU ARCHIVES

With the game evolving, the selection criteria for ‘keeper-batters have changed, and Russell blames this on a lack of understanding of the craft. “I don’t think there’s an understanding of the importance of wicketkeeping anymore. You look at Ben Foakes, who played a year or two back and kept wickets brilliantly and scored runs as well. But he didn’t play thereafter because he did not bat aggressively enough. So, now the priority is that a wicketkeeper can’t just score runs. He has to score runs aggressively,” he says.

However, Russell is not willing to blame T20s. “In T20s, you can play your best keeper. There is such a fine line, where every run, every save matters. So, in such a situation, you should play your best ‘keeper, as he can make the difference. It’s just a case of selectors being greedy,” he says.

“There’s no way a wicketkeeper is going to bat down at No. 9 or No. 10 now. That’s never going to happen again. The selectors now pick ‘keepers based on how good his batting is. So, even if he is a good wicketkeeper, the number one big question is how good is his batting going to be before they actually stick with a wicketkeeper?”

This approach, Russell believes, has been in the system long before T20s came into existence. “It was happening when I was playing. There was no T20 back then. The selectors don’t appreciate the importance of the wicketkeeper’s skill. And they’re trying to cut corners and trying to get extra runs,” he says.

Being someone who loves speaking his mind, Russell has a word of caution for budding wicketkeepers: “I would say, ‘Lad, just concentrate on your batting, otherwise they are not going to pick you. Because some aggressive innings is what would get you noticed. So, you have to find a way of making sure that you bat well and you’re a top batter.’ It’s a bit like being an all-rounder,” he says.

“Ian Botham told me once, ‘When I’m bowling, I think I’m a frontline bowler. And when I’m batting, I think like a frontline batter.’ It’s a similar story for keepers now. You need to make sure both of your skills are as good as they can be. But if you want to get in the team, runs are the key.”

More than two decades after hanging up his gloves, Russell still feels the sting as wicketkeeping’s craft loses its sheen. Then, with a smile, he says, “That’s how the time is…” before turning back to his unfinished portrait.